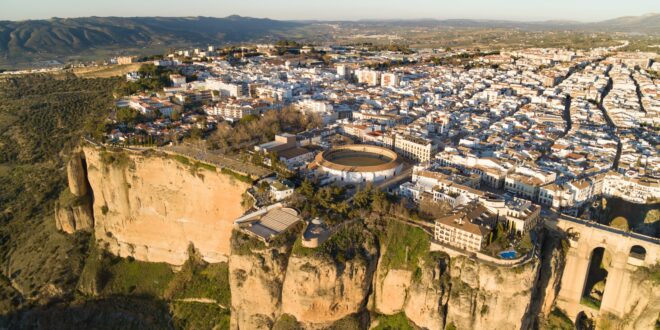

BUILT high above a yawning gorge in the sunbaked mountains of Málaga province, Ronda doesn’t so much sit in the landscape as command it.

Hemmed in by sheer cliffs and ringed by whispering olive groves, it’s a place of poetry and peril — the kind of town that feels suspended in time, hanging between heaven and earth.

The Spanish like to say it’s where ‘it rains upwards and birds fly beneath your feet’. That’ll make sense the first time you step onto the Puente Nuevo, the jaw-dropping 18th-century bridge that vaults 100 metres over the chasm carved by the Guadalevín River. It’s more than just a feat of engineering — it’s a metaphor for Ronda itself: dramatic, historic, and just a little bit mad.

One thousand years and more of history

The story of Ronda began long before any bridges were built. The Celts called the settlement Arunda. The Romans followed, building a city at nearby Acinipo — now a windswept archaeological site where sheep graze between theatre ruins and stone seats worn smooth by time. Later came the Moors, who left their fingerprints all over the city – in its labyrinthine old town, its soaring walls, and its perfectly preserved baños árabes The best in Spain are (Arabic baths).

By the time the Catholic monarchs arrived in 1485, Ronda had already lived several lives – Celtic, Roman, Muslim – and it would go on to play a key role in later revolts, resistance movements, and even a touch of bandit folklore. The old city of Ronda still holds on to the edge of the cliff, as it has for centuries, in the flickering, warm light of the late afternoon.

The city that inspired poets, outlaws and more

Ronda doesn’t lack admirers. The likes of Rilke, Juan Ramón Jiménez, and even Orson Welles sang its praises – quite literally in some cases. Welles so loved this place he decided to scatter his ashes there. Ernest Hemingway spent summers here and immortalised its brutal bullfighting traditions, wild mountains backdrop, and gory customs. For Whom does the Bell Toll?

Ronda is a place of romance, but not in the traditional sense. This is a land of whitewashed villages and twisted alleyways, of dusty trails leading to ancient watchtowers, and of brutal beauty — both natural and manmade.

Nature, raw and untouched

Tajo de Rondo, the dramatic gorge which divides the town in half, is at its heart. It is a geological marvel, officially declared as a Natural Monument. Peregrine falcons and kestrels live there, along with the eerie cries of the eagle-owl. The old Moorish quarter is on one side, while the newer part has shops, bars, and the famous bullring.

Walk the length of the gorge, linger in the shaded avenues of the Alameda del Tajo, or descend to the river itself via ancient staircases – and you’ll see why nature lovers and adrenaline seekers alike are drawn to this Andalusian hideaway.

Into the Serranía: White villages and prehistoric caves

Step outside Ronda and you enter another world entirely – the Serranía de Ronda, a wild, untamed stretch of mountains that feels carved from legend. Andalusia is at its purest: jagged peaks of limestone, winding tracks for mules, and quiet towns where the time flies by.

This region is a walkers’ paradise. Ancient footpaths weave through forests of cork oak, past crumbling towers, and along ridgelines which seem to reach the clouds.

In spring, the hills are ablaze with wildflowers. Vultures circle overhead and ibex clamber across distant cliffs. Keen hikers make a beeline for the Sierra de Grazalema Natural Park – the wettest place in Spain, oddly enough – while the newly minted Sierra de las Nieves National Park dazzles with deep gorges and twisted pinsapo pines found almost nowhere else on Earth.

But the magic here isn’t just in the scenery – it’s in the villages that cling to the hillsides like bleached coral. Grazalema, Zahara, and Gaucín may get the postcards, but don’t skip the lesser-known spots like Montejaque or Benaoján, where labyrinthine lanes and stone cottages lead you down to cool, spring-fed pools.

Cueva de la Pileta is one of Spain’s most impressive prehistoric sites. A local farmer discovered the cave in 1905. It’s a candlelit cavern with bison, deer and fish scrawled on it in ochre, charcoal and other pigments. No spotlights, no gimmicks – just the quiet awe of standing where Paleolithic artists once stood. Small groups of descendants from the same family as the ones who discovered the cave are there to guide you. Their voices echo softly in the dark chambers.

It’s the kind of place – like Ronda itself – that burrows deep into the imagination and stays there.

Taste the food that comes from where it is grown

In Ronda, meals come steeped in local flavour – both literal and cultural. Try them all rabo de toro (oxtail stew), Migas con ChorizoOr the mountain cuisine’s game meats. The wines of the Ronda region, grown at surprising altitudes, are making quiet waves in the Spanish wine world – and pair beautifully with a view over the gorge.

You can also try the sweets made by the Franciscan nuns, such as yemas or caramelized delights. You don’t have to be religious in order to enjoy their baked goods.

Ronda (Málaga)

The last word

Ronda does not have a check-list. It’s not about ticking off sights – although it has plenty. Slow down, soak up the scenery and let the past speak to you in the olive groves and stone walls. Come for views, history or food. Stay because – like Hemingway, like Welles – something about Ronda lodges deep in the soul.

What you need to know

Trains run from Málaga and Sevilla to Ronda. Accommodations range from hotels on the cliffs to charming guesthouses located in the old city. You can find more information at andalucia.org

Costa News Spain Breaking News | English News in Spain.

Costa News Spain Breaking News | English News in Spain.