Imagine an entire year of rain in only three and a half hours. Every spring shower, every winter burst — delivered in a single downpour. This is what happened six months ago in the hills around Valencia, Spain’s south-east. October 29, 2015, was the deadliest flood day in Europe since decades. At least 227 died.

The mud, wrecked vehicles, and high-water marks were still visible when I visited Paiporta. As the ground is still wet, it’s not worth repainting homes until after the summer.

Perhaps the most lasting legacy of the floods is the drive to prosecute the people in charge. Spain was one the few nations to imprison former bank executives in the wake of the financial crises. Now it could — possibly — jail former public officials for their emergency management.

When can a natural catastrophe be attributed to human activity? When is human error so grave that it violates the law? Nuria Ruiz-Tobarra, a Valencian judge, is investigating the questions in a manner that would embarrass any British public inquiry. Her first conclusion was that, “the damage could not have been avoided but the deaths might have,” The torrents that raged in Paiporta may have been biblical, but the water only rarely reached the top floors of the buildings. There was enough safe space if people knew to leave their cars or ground floor homes.

Video footage of the flooding.

Los Angeles has also been asking the same questions following the unprecedented January fires. Climate change exacerbated the drought. But why were city firefighters not pre-deployed like they were in 2011? Two reality TV stars and some residents are suing the City of Los Angeles for problems with its firefighters’ water supply.

The impact of any disaster — perhaps except for an extinction-event asteroid — is shaped by human actions. The number of disasters that killed people has dropped steeply over the last century. It went from around 500,000 per year in the 1920s-30s to about 60,000 in the 80s-90s.

We learned to protect ourselves. We created flood barriers, warning systems and other things. Yet, such advances make the cost of disasters for victims today even more horrifying.

It’s difficult to blame humans for a disaster if they don’t prepare and warn. But legally, it can be hard to do so. German prosecutors did not pursue charges against an official who was absent during the deadly floods of 2021 because they believed that failures were widespread. After the L’Aquila quake of 2009, seven Italian scientists and officials initially were convicted of manslaughter because they failed to warn about the dangers. Only one official’s conviction was upheld because he incorrectly claimed that earlier tremors did not increase the risk of major earthquakes. “So, we should drink a glass of wine?” Before the deadly earthquake, a journalist asked. The official answered, “Absolutely.” He received a two-year suspension.

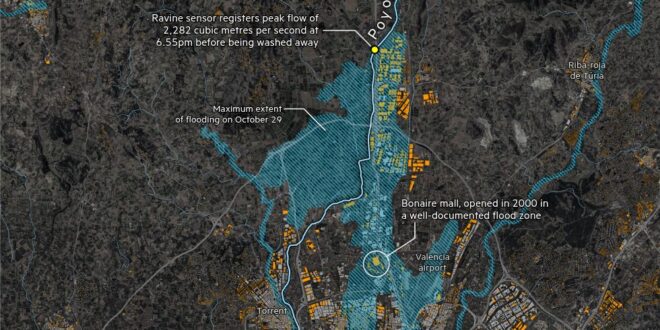

Valencia floods seem to be a very clear instance of incompetence. Forecasts warned of heavy rainfall the weekend before. All classes at the University of Valencia were suspended. The regional government did not send out an alert to residents until 8.11pm, October 29, but it was only a few hours later. The stream in Paiporta burst it’s banks by then and many of 227 victims were dead.

Judge Ruiz is investigating Salomé Pradas, the regional official in charge of sending emergency alerts, and the regional emergency secretary Emilio Argüeso (both fired shortly after the floods) on suspicion of manslaughter. In her testimony earlier this month, Pradas acknowledged that she had no prior experience in handling emergencies.

California’s Pacific Gas and Electric, a utility company, agreed to pay victims $13.5bn for the role of its equipment in wildfires. In 1996, flooding in the Spanish Pyrenees killed 87 people. The regional government and the environment ministry were ordered to pay €11.3mn compensation for having allowed a campsite in a flood zone.

Natural disasters could be seen as a way to strengthen democracies: by bringing them under public scrutiny. Amartya Sen, the Nobel Prize-winning economist, famously claimed that famines are caused by humans. Episodes such as those of the Bengal famine in 1943 were more likely to be caused by a decrease in food supplies than by a lack of access to food. “There has never been a famine anywhere in the world that is functioning democracy,” wrote Sen. India hasn’t experienced a major famine ever since its independence.

The failures of authoritarian regimes to respond to natural disasters were particularly pronounced. Mexico’s poor response to the 1985 earthquake, which saw it rejecting international aid early on, accelerated the fall of the one-party system.

Climate-driven catastrophes reveal the democratic shortcoming that is long-term plan failure. In Valencia, the regional leader Carlos Mazón abolished a nascent emergency unit a year before the floods, as part of an attack on bureaucracy. His government, like many others around the globe, has encouraged building in flood zones and avoided climate action. According to World Weather Attribution, heavy rainfall events such as the one responsible for the Valencia floods today are about twice more intense and likely than they were in pre-industrial time.

The blame game is a distraction. Politicians who deny climate-change, like Trump, may focus on local factors such as Los Angeles’ water supply while ignoring underlying causes. Valencia’s survivors are right to focus on both short-term mistakes and the long-term climate neglect. They are in no doubt that theirs was partly a human disaster: there have been six marches calling for the resignation of Mazón, who spent much of the key afternoon of October 29 having lunch with a journalist. (Others, on the right, have blamed Spain’s socialist prime minister Pedro Sánchez, although Judge Ruiz has stated that the emergency alerts were a regional responsibility. The king of Spain is no longer the target. He was pelted by mud days after the tragedy.

Depending on who you ask, Paiporta today is either half-recovered (or half-abandoned), or it’s still being rebuilt. Many homes and shops on the ground floor are still ruins. Some older shop owners will not return. Paiporta, just a few metro stops from Valencia’s main station, is still being fixed. A bus is in place to replace the line.

I met a woman called Cristina Marí Andreu, whose toy shop was destroyed by the floods. Thanks to a quick grant from a supermarket, she was able to reopen her shop and buy a brand new car with public funds. She remained furious. “They ignored us for five days. “We didn’t have electricity or water,” she said. She shared a waterless bathroom with five of her relatives. It was a deeply uncomfortable experience to receive handouts. What I really want to do is go back six-months. I want the same thing I had.”

Officials must act more quickly and better to prevent disasters caused by climate. Valencia’s officials did not pass the test. But it’s questionable whether even competent authorities can satisfy residents’ demands — or whether, as with the Covid pandemic, they will almost inevitably make mis-steps.

In a world of disasters, just as in the case of a pandemic outbreak, there are losers. People who pay taxes to finance climate action. People who don’t want to live near flood zones. Or people who lose their homes in extreme events. Covid has undermined the trust of many people in institutions. It may be difficult for elected officials to deal with the possibility of more semi-natural catastrophes.

Henry Mance is FT’s Chief Features Writer

Find out about our latest stories first — follow FT Weekend on Instagram You can also find out more about the following: X. sign up Get the FT Weekend every Saturday newsletter

Costa News Spain Breaking News | English News in Spain.

Costa News Spain Breaking News | English News in Spain.